My sister, aptly blogging at @QuilledSister, writes short stories on her blog. Read her stories! She is a good fiction writer. I am not. But sometimes I get inspired to write a response. This is one of them.

Original Story: Lament

My Story

I knew her the moment she walked in, of course. Her glamours are literally the source of the word, but she has absolutely no tolerance for error. When a woman that perfect enters your bar, you’re in danger.

So I kept on serving the three girls who’d been there all afternoon. They’d started with mimosas at lunch and just kept going. They were easy money for someone like me—a smile here, a wink there, keep the sleeves rolled up just enough that they could see I’m mostly muscle—and I was sure my bed would be warm tonight. It almost always was.

The man in the leather duster kept staring at me like he knew something, but didn’t quite know what. He stared at the beer, too—a brown ale, served too cold at his request—and didn’t say much.

The woman took an easy seat at a table, speaking low to one of our waitresses, presumably a drink order.

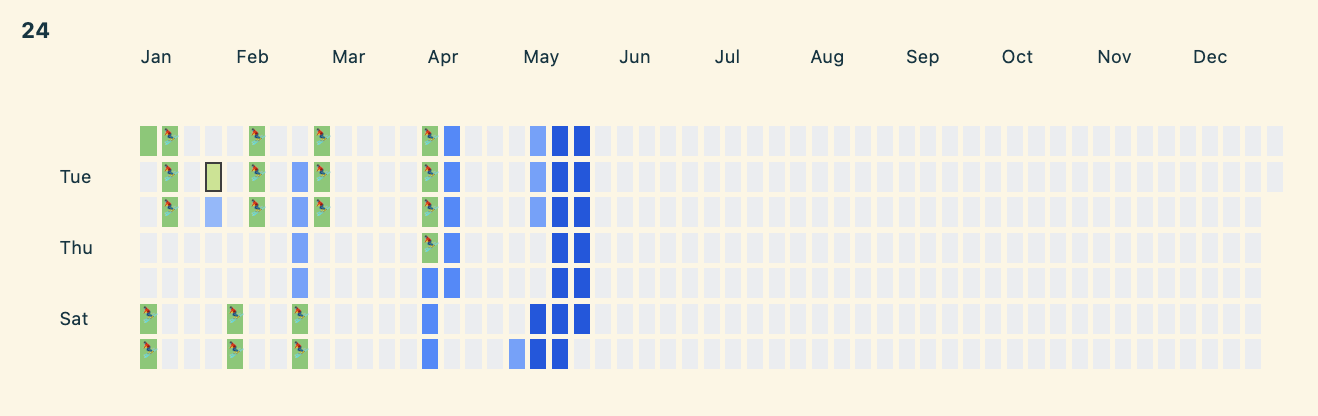

I was still trying to work out what she could possibly order when she stood up to take the stage. Tuesdays are spoken word open mic nights here at Goodfellow’s, and it was always fun to see who worked up the courage to walk up front and pour out their notebook into the mic.

Always some English majors, and some wannabe English majors, and some dropout English majors. Sometimes one of the overachieving STEM kids who couldn’t stand not being good at everything. Usually a few loners who really did want to be poets.

No one like this had ever taken our stage. Every eye followed her—mine included. How could you not stare at that perfect ass?

I don’t mean Venus de Milo or Jessica Alba or Flo-Jo. I mean, the cosmic ideal of ass. Yes, her heels were stunning, as were the legs they supported. Somehow even the muscles of her back through the blue off-shoulder top were captivating. And her shock-white hair competed for attention with her sinuous neck. But that ass… one flexed buttock could have sent the whole room into an orgy.

She didn’t, of course. Her control was total.

Her voice was what surprised me the most. It sounded… normal. Almost relaxed. When you’ve known her as long as I have, you kind of get used to the intense radiating power of her voice, even when she’s speaking in a whisper.

But tonight was like she’d found a new gear. A lower one.

Good evening ladies and gentlemen. Tonight, I want to give a longwinded shoutout to my man, Mercutio.

ahem…

She did not need to clear her flawless opal-jeweled throat.

She’d been practicing.

I was in trouble. We were all in trouble.

Could steal your girl

But he doesn’t want her,

Tarnish his honor

But don’t squander the love scholar.

The original bad bitch

A casual curse witch…

Her poem wasn’t great. I mean, it was delivered with the kind of vocal skill usually reserved for EGOT winners and Morgan Freeman. But the Bard she ain’t.

Not that it mattered; between her body and her voice, I’m not sure anybody but me could hear the words. Well. That guy in the duster—something told me he didn’t miss much.

She finished, accepted the polite applause and ubiquitous catcalls, and glided to the bar.

I turn on the charm, playing up the part of bartender, hoping she’ll leave me alone. Believe me, you don’t want her attention.

“What’ll it be, my rhyming mademoiselle?”

That’s the ticket, overboard on the flirting; nobody in their right mind would flirt with her.

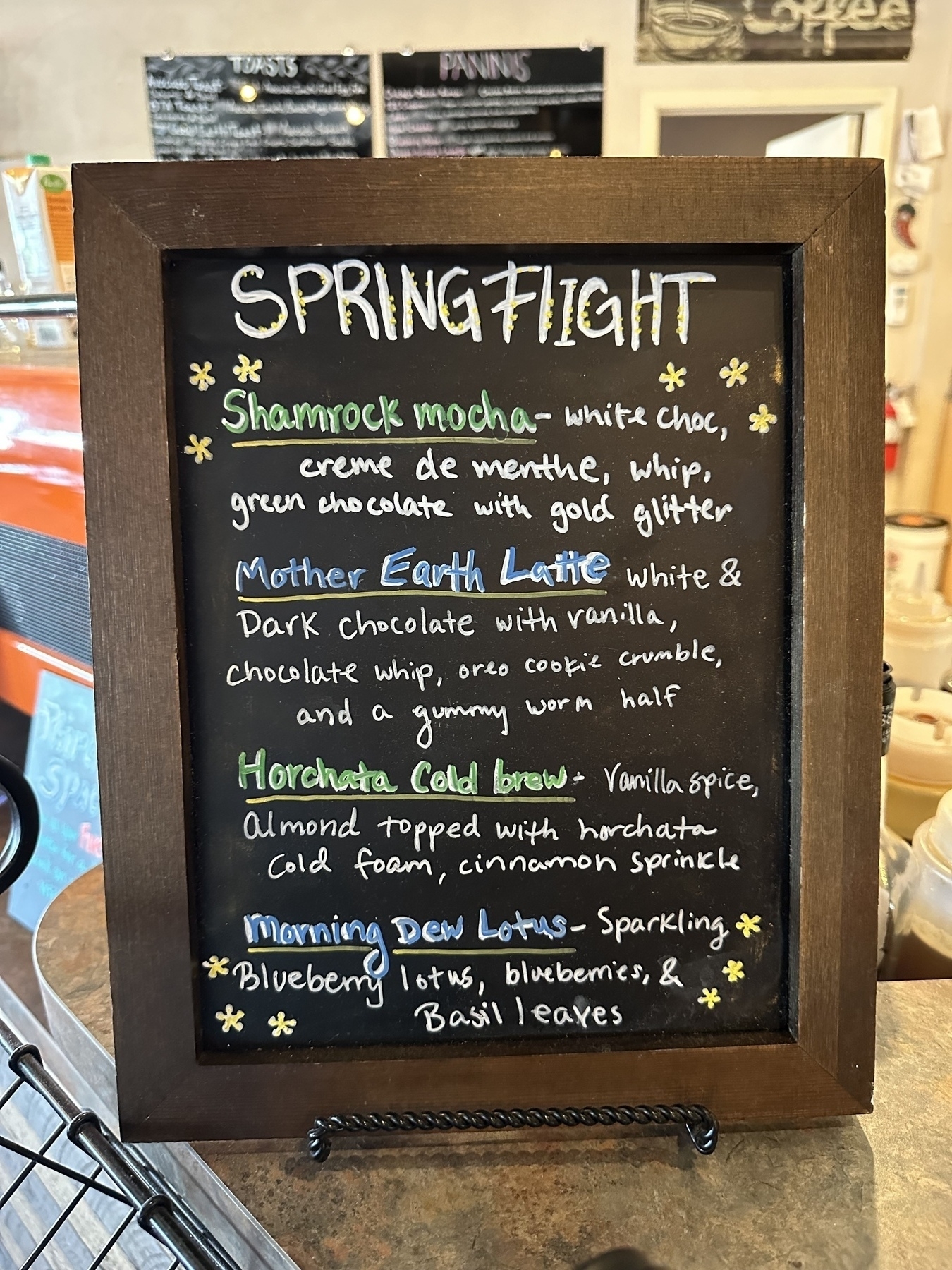

“A friend of mine recommended something, but I can’t quite remember the name,” she purrs, leaning in more than necessary, “it’s a bubbly one, with a country in it.”

Dangerous. She’s just as dangerous from the front as the back—more so, with those damn eyes—and she’s leaking power. She must have enjoyed herself up there to slip like this. I feel myself drowning in her, and only centuries of practice and a wrenching act of will keep me breathing.

“A whole country? I don’t know if I can fit that in a glass,” I say as I pray she’s too distracted to notice my brief hiccup. Probably every male she’s ever met has had that problem and she’s used to it. Every female, too.

I start making the drink she’s obviously referring to as she politely chuckles at my joke.

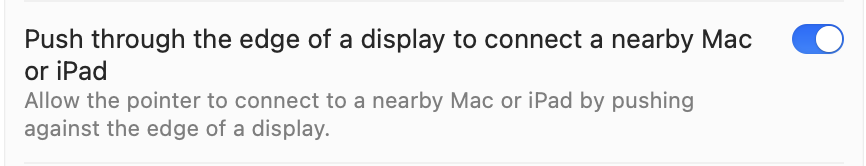

We are playing a terrifying game. One that I can’t win. Only survive.

Out of the corner of my eye, I see the man in the duster suddenly attentive to our conversation, a hand reaching below the bar. Stay calm, man, you can’t handle this one.

“You’re looking for a French 75, I believe,” I say, sliding it into her hand and winking.

“Yes! That’s…”—she starts her next rehearsed line a moment before realizing that I’ve skipped a step and already given her the drink.

Not smart. I should have played along. But I couldn’t help myself. It’s who I am.

“I’ll be back to hear how perfect it is,” I croak, and race back to those giggly girls, suddenly desaturated in comparison. At least none of them will kill me in my sleep.

I wait for her to take a sip, appearing to focus all my attention on the ladies in front of me. The moment she turns back to the bar, I’m in front of her. Can’t leave her alone for long.

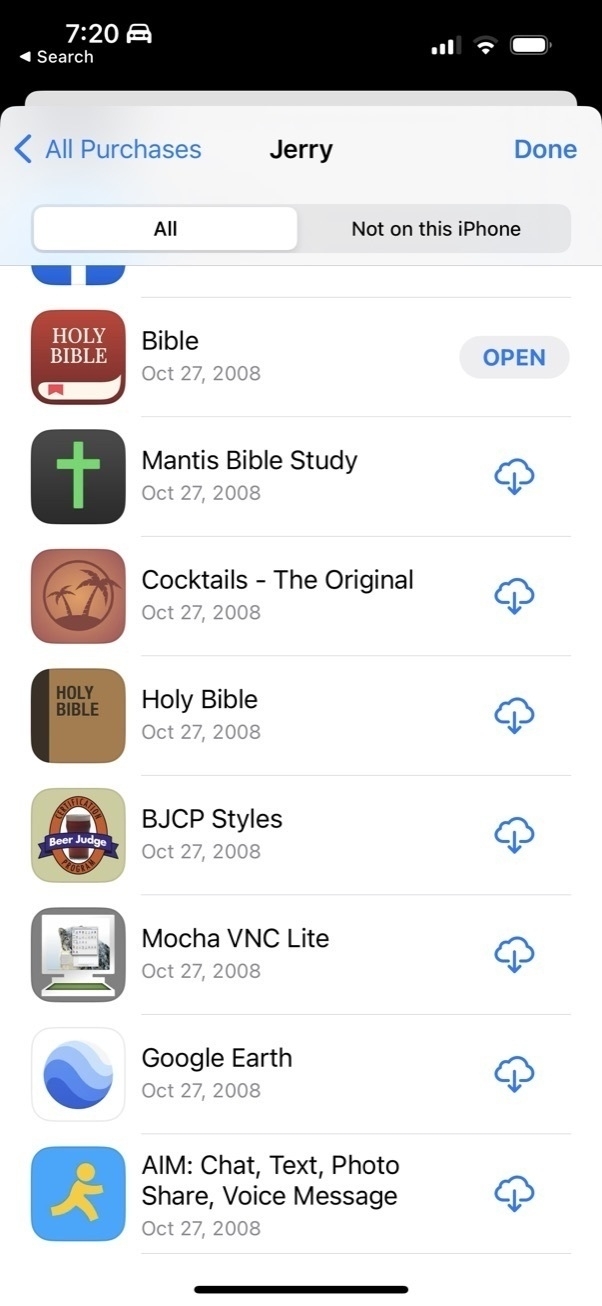

“You’re becoming a bit of a regular,” I venture, thinking she might take the bait and tell me what the hell she’s doing here. Again. “I can add you to the local’s tab lists if you’d like. Gets you, ah, 10% off on Thursdays.”

A vulpine look fades as she finishes turning from studying the crowd, identifying and dissecting my hook, analyzing the opportunities, and eventually deciding not to play tonight.

“Sure, put me in there, big guy.”

Well, nothing ventured, nothing gained. One more try.

“Lucky for us! And what’s the pretty name of the pretty lady?”

She answers, and the power of her answer rocks me back a bit. I stutter, pretend I couldn’t hear over the idiot up on stage.

“Mag? As in Maggie?”

Please don’t say your name again.

“Mab, my dear Puck. As in Queen.”

Shit.